Second (after a volume on Oxford) in a new series from Amberley, this volume is the author’s third book on the archaeology of Manchester, following his earlier Manchester: The Hidden History (Nevell 2008) and Manchester at Work (Nevell 2018). The unenviable task of choosing twenty sites which sums up an area is one where there will always be disagreement - as it should be. This volume covers the area (mostly) within the boundaries of the Manchester City Council area. It concisely introduces the archaeology of the Roman site in Britain which has the most known Roman roads converging on it and the prototypical industrial city. There is more to Manchester’s archaeology than these two periods, but they loom large in the selection of sites. Of the twenty sites, one is prehistoric, five are Roman, two Mediaeval and the remainder are post-Mediaeval [1]. The sites are discussed in roughly the chronological order of their archaeological investigation, from Bruton’s work in the Roman fort in 1906-7 to the 2017 Reno nightclub excavation.

The choice of sites reflects – and celebrates – forty years of archaeology within Manchester, initially at the University of Manchester and latterly at the University of Salford [2]. Many of the sites chosen are part of innovative projects undertaken at those Universities, as well as archaeology ahead of development and community archaeological projects, and, sometimes, as a combination of all three. These have lead to a broader understanding of Manchester as more than just a Roman foundation which became the centre of cotton spinning. Beginning with Professor Barri Jones’ work at Deansgate, there have been extensive investigations of the dwellings of ordinary people, as well as the grander houses of the gentry. The varied industries of the city, not just cotton, have been investigated; the Mediaeval centre of Manchester has been studied and great efforts have been made to try to make the archaeology accessible and comprehensible to the communities who now live in their areas. Sites which were in use in moments of great social change are included by the investigations of Hulme Barracks, used by the cavalry at Peterloo (Dig 17) and the late 20th century multi-cultural Reno nightclub in Hulme (Dig 20).

The choice of sites obviously reflects the author’s long collaboration with Norman Redhead (formerly County Archaeologist at GMAU and then Heritage Management Director at its replacement the Greater Manchester Archaeological Advisory Service (GMAAS) and recently retired). This book demonstrates how these archaeologists and others, especially Barri Jones of the University of Manchester and Robina MacNeil, the first County Archaeologist at GMAU, have contributed massively to the understanding of the archaeology of the city. The author worked for the (also defunct) University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, formed from GMAU, and when that Unit was closed he set up the replacement Centre for Applied Archaeology (CFAA) at the University of Salford, welcoming most of the former GMAU staff there - as GMAAS - a few years later, following the closure of GMAU. The book is also a celebration of these groups, with their emphases into working both on planning based archaeology and community archaeology as well as producing high quality research. It is also a celebration of how the people of Manchester have been invited to take part in excavations and projects, helping re-write the history of their city, involvement which was promoted by many people, with Councillor Paul Murphy being a notable and persistent advocate.

A further observation from studying this volume is that despite extensive later re-development and truncation, there can often be found surviving archaeology below ground to surprising depths, especially on sites with industrial processes.

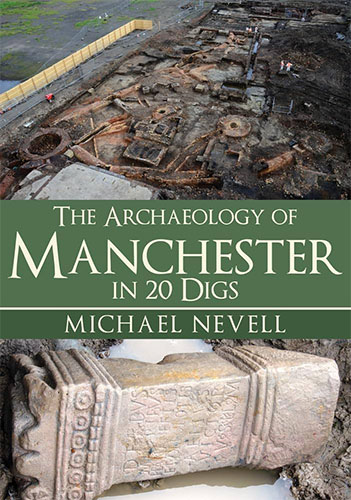

Several of the important excavations in this book are otherwise not published elsewhere, existing as ‘grey literature’ and so this volume is important in that it brings the information out of the archive and Historic Environment Record and helps it reach a wider audience. Other sites are more famous, or indeed infamous, such as the inner rubble core of the eastern gateway [3] (Nevell 2020: 21, illustrated on pg 8), as formerly the only visible part of the Roman fort.

There is unfortunately a repetition of the error from one of the author’s earlier books on the archaeology of Manchester (Nevell 2008: 28) of the name of the second [4] known Roman from an inscription on pg 58, with the correct name, Aelius Victor given in the transcription a few pages later (pg. 61).

The sites chosen are a very good introduction to the archaeology within the city boundary. However, Manchester is only half of the story - over the Irwell lies Salford, where equally interesting work has been carried out in parallel to the work discussed in this book. Lacking Manchester’s fame it may not be given a volume in this series, but recent publications on work on the historic Mediaeval core at Greengate (Gregory and Miller 2015), the site of the New Bailey Prison (Reader and Nevell 2015) and Castle Irwell, which discusses Salford’s archaeology from prehistory to the modern era (Reader 2018) can give a complementary flavour to this book.

[1] Compared to the other periods little later prehistoric and Anglo-Saxon archaeology is known from the city. For the latter there is long-lost pottery, some coins and place names (Morris 1983) and an enigmatic ditch feature discussed recently in the author’s blog (Nevell 2020).

[2] For avoidance of doubt, I had the pleasure of working with the author whilst working for the now defunct Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit (GMAU) from 2008 until its closure in 2012. Some of the work showcased in this book is very familiar and brings back happy memories. In particular, being present when the photograph on pg 5 was taken, a breathtaking view across the city as seen from a high floor in the Beetham Tower and arguing for more work at Ashbury’s with colleagues, because there might be interesting below ground archaeology, which turned out to be Dig 16 in this book.

[3] This was described in damning terms by A J P Taylor, in a review of Manchester for a series on the world’s great cities: “Manchester had a Roman foundation, though not worth lingering on. Its only standing structural remains, the fragment of a wall in a goods yard at the bottom of Deansgate, must rank as the least interesting Roman remain in England, which is setting a high standard!” (Taylor 1957, cited in Jones 1974: 29). The subsequent archaeological discoveries have proved Taylor wrong, in that despite Manchester’s Roman archaeology having suffered much truncation and destruction, there is much to linger on and ponder, as is shown in the book under review.

[4] The first named Roman from Roman Manchester, Lucius Senecianius Martius, was named on an altar discovered in 1612, found further to the north on the other side of the river (RIB 575).

References

- Gregory, R. and Miller, I. 2015 Greengate. The Archaeology of Salford’s Historic Core. Greater Manchester’s Past Revealed 13 (Lancaster : Oxford Archaeology North).

- Jones, G.D.B. & Grealey, S. 1974 Roman Manchester (Altrincham, Manchester University Press).

- Morris, M. 1983 The Archaeology of Greater Manchester vol.1: Mediaeval Manchester, a regional study (Manchester, Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit).

- Nevell, M. 2008 Manchester: the Hidden History (Stroud, Tempus).

- 2018 Manchester at Work (Stroud, Amberley).

- 2020 “Landscape Longevity and the Continuing Mystery of Nico Ditch – Manchester’s First Great Ditch” https://archaeologytea.wordpress.com/2020/01/31/landscape-longevity-and-the-continuing-mystery-of-nico-ditch-manchesters-first-great-ditch/ (Accessed 03/07/2020).

- Reader, R. 2018 Castle Irwell. A meander through time. Greater Manchester’s Past Revealed 22 (Salford, Salford Archaeology).

- Reader, R. and Nevell, M. 2015 “New Bailey, Salford. Prison’s industrial revolution” Current Archaeology (December 2015) 309: 32-38.

- RIB 575 https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/575 (Accessed 03/07/2020).

- Taylor, A.J.P. 1957 “The World’s Cities (1): Manchester” Encounter (March 1957), 3-13.